|

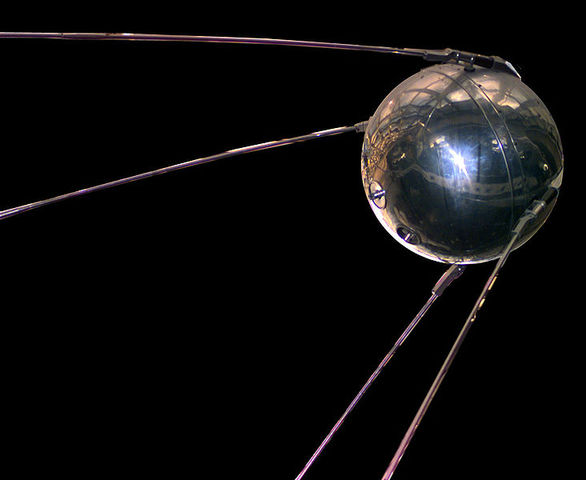

| Sputnik 1 |

|

| Darn kids always stirring up trouble! |

(Listen to Sputnik here. It's spooky!)

By today's standard, the US satellite Explorer I was also primitive, but it did carry a small number of scientific instruments and was the first spacecraft to detect the existence of the Van Allen radiation belt, giving some hint of the great scientific strides which would be taken with space exploration.

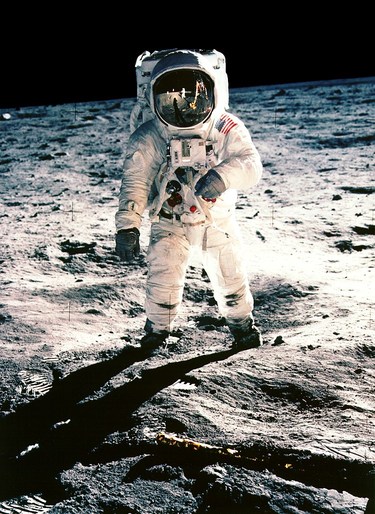

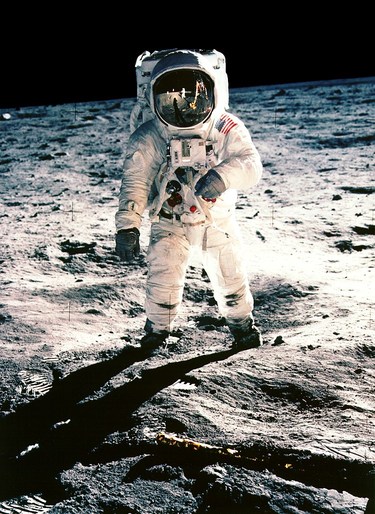

President John F. Kennedy kicked the space race into high gear when he announced America's intent to be first to land on the moon. JFK famously called the moon mission "the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked."

A generation of students was galvanized. How could they not be moved by the challenge to be a part of that adventure? The benefit to the US was great -- where the US had once lagged in science, technology, engineering and math graduates, the space race produced a long procession of these who helped make America the leader of the scientific and economic world.

But the supply of new scientists and engineers has fallen off in recent years, and as the average age of science and engineering employees crept inexorably towards retirement age, former President Bush established the Constellation program, a multistep NASA plan designed to take manned space exploration all the way to Mars. But going to Mars was only one of the intended benefits: It was also made to once again motivate a generation to dedicate themselves to STEM fields.

But the supply of new scientists and engineers has fallen off in recent years, and as the average age of science and engineering employees crept inexorably towards retirement age, former President Bush established the Constellation program, a multistep NASA plan designed to take manned space exploration all the way to Mars. But going to Mars was only one of the intended benefits: It was also made to once again motivate a generation to dedicate themselves to STEM fields.